by Elizabeth Klett

Text | Notes | Works Cited | Cite | Related Content

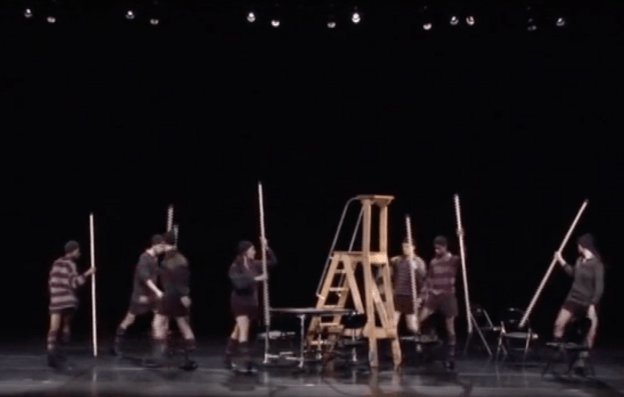

Agincourt, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

The opening moments of David Gordon’s 2004 modern dance work Dancing Henry Five immediately challenge the spectator to make sense of the piece in relation to Shakespeare’s play. The stage is strewn with seemingly random pieces of furniture: a desk, an empty rolling garment rack, stacked folding chairs, and a wooden A-frame ladder. There are a few rubber balls lying around, and when the dancers enter, they are dressed in what appear to be rugby uniforms: striped jerseys, shorts, black sneakers, and knee socks. They walk across the stage apparently arbitrarily, entering and exiting casually, or turning around and crossing back the other way. They hold up placards as they move around, each with a single word written on it: “Dancing,” “Henry,” or “Five.” They spell out the name of Gordon’s piece, but not in a systematic way, since there are multiples of each word, and the dancers never stop moving, nor do they put the words together to form a single, complete title. The title itself suggests Gordon’s irreverent approach to his subject; “Henry Five” is a casual appellation, distinctly not “Henry the Fifth,” as the monarch is usually addressed. The addition of “dancing” to his name possibly implies the futility of attempting to render his story through movement, rather than through dramatic poetry. Although the opening strains of William Walton’s majestic score for Laurence Olivier’s propagandistic 1944 film version of Henry V accompany Gordon’s opening scene, the feeling overall is one of distance from, rather than proximity to, the “Shakespearean original.”1

This essay provides a close reading of Gordon’s piece to explore the ways in which modern dance adaptations can defamiliarize Shakespeare. In creating this argument, I am using dance scholar Sally Banes’ appropriation of literary critic Victor Shklovsky’s concept of defamiliarization, which, at least in part, makes “familiar things strange” (Reinventing 5). While Banes uses this idea to characterize American modern dance of the 1960s, I would like to extend the idea into the still under-theorized arena of dance adaptations of Shakespeare, contending that Gordon’s Dancing Henry Five is an example of how choreographers can make Shakespeare strange, new, and challenging. His work defamiliarizes Shakespeare by defying narrative coherence, primarily through the devices of repetition and meta-theatricality. He prioritizes choreography over narrative, placing less emphasis on telling the story and more on the expressive potential of the dancer’s body and movements. The piece incorporates all the hallmarks of Gordon’s technique: “spoken narration, an informal choreographic style of ordinary gestures and basic walking around, and an irreverent tone laced with wit and irony” (Kaufman). While his use of Walton’s music suggests an inter-textual relationship with Olivier’s film version to some extent, Gordon also literally takes his cue from the structure of the score more than from the visual language of the movie. Choreography and music work together in his re-vision of the play, taking up the Chorus’ injunction to work on the spectator’s “imaginary forces” (Prologue 18). Gordon and his own Chorus (embodied by his wife, dancer and actress Valda Setterfield) 2 spur their audiences to think analytically and feel kinesthetically the potential of dance to defamiliarize Shakespeare’s play.

Modern dance developed, at least initially, out of a desire to challenge the perceived rigidity of ballet technique, as well as its emphasis on narrative forms, particularly its uses of pantomime to tell stories. As Alexandra Kolb observes, modern dance “practitioners devised radically novel movement styles that far exceeded the limitations then placed on ballet’s kinetic range” (2). American modern dance pioneers wanted to highlight the expressive potential of the body as “dance’s essential component” and its capability of “unif[ying] movement and meaning” (Morris 19). In the 1920s and 1930s, ballet was “anathema to modern dance since it was assumed to be at odds with modern dance’s mission” (Morris 15). Yet choreographers like Martha Graham began to incorporate ballet technique into their work, while George Balanchine later integrated modern technique into the repertoire of New York City Ballet, revealing that the two forms were not as distinctive or separate as some might wish. Both fields’ relationships to narrative were vexed. Since modern dance championed the idea of movement for its own sake, its choreographers tended to reject the focus on narrative (and particularly pantomime) in classical ballet.

Yet early modern dance also had strongly expressionist tendencies, “anchor[ing] movement to a literary idea or musical form” (Banes, Terpsichore 15). Works like José Limón’s The Moor’s Pavane (1949) oscillate, as Gay Morris has shown, between a delight in the possibilities of “‘pure’ dance movement” and the communication of plot and characters in relation to a Shakespeare play – in Limón’s case, Othello (28). “Postmodern” choreographers like Merce Cunningham challenged this narrative tendency, particularly the ideology of universalism that often underpinned it. Instead they “became increasingly interested in plumbing the expressive and aesthetic potential of ordinary movement and situations. In their lights, the dancing body was defined by its very movement, and not, therefore, relative to a normative standard or type suggested by a given character or role” (Kowal 11). When narrative became “reinstalled in dance” in the 1970s, it also became postmodern in its tendencies, “distanced by techniques of alienation and reflexiveness” (Banes, Terpsichore 18).

Gordon is strongly associated with the postmodern strain of American modern dance, and began his career working with avant-garde choreographer James Waring in the 1960s. With Waring and other radical dancers, he founded the Judson Dance Theater (1962-1964) 3 and later co-founded the experimental troupe Grand Union (1970-1976). Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his background, Gordon’s Dancing Henry Five takes a distancing stance on his literary source material, revealing his embeddedness within American postmodern dance. Although Gordon’s piece can be read in relation to Shakespeare’s play, it also undercuts and problematizes that reading process. Gordon accomplishes this by challenging narrative coherence, structure, and linearity. He also embraces confusion, contradiction, and ambiguity, openly acknowledging the problems inherent in “doing” Shakespeare in dance.

Setterfield, as Gordon’s Chorus, highlights those problems from her very first entrance; she climbs the A-frame ladder to address the audience in a wry, matter-of-fact tone, openly admitting that what they are about to see will not look anything like Shakespeare’s Henry V, particularly since it will only consist of one act running about an hour. Further, the limited personnel involved necessitates a drastic reduction in the story: Setterfield tells the audience that they had to cut “all the lords of the English court, and all the lords of the French court. We are, after all, only seven dancers, three dummies, and me.”

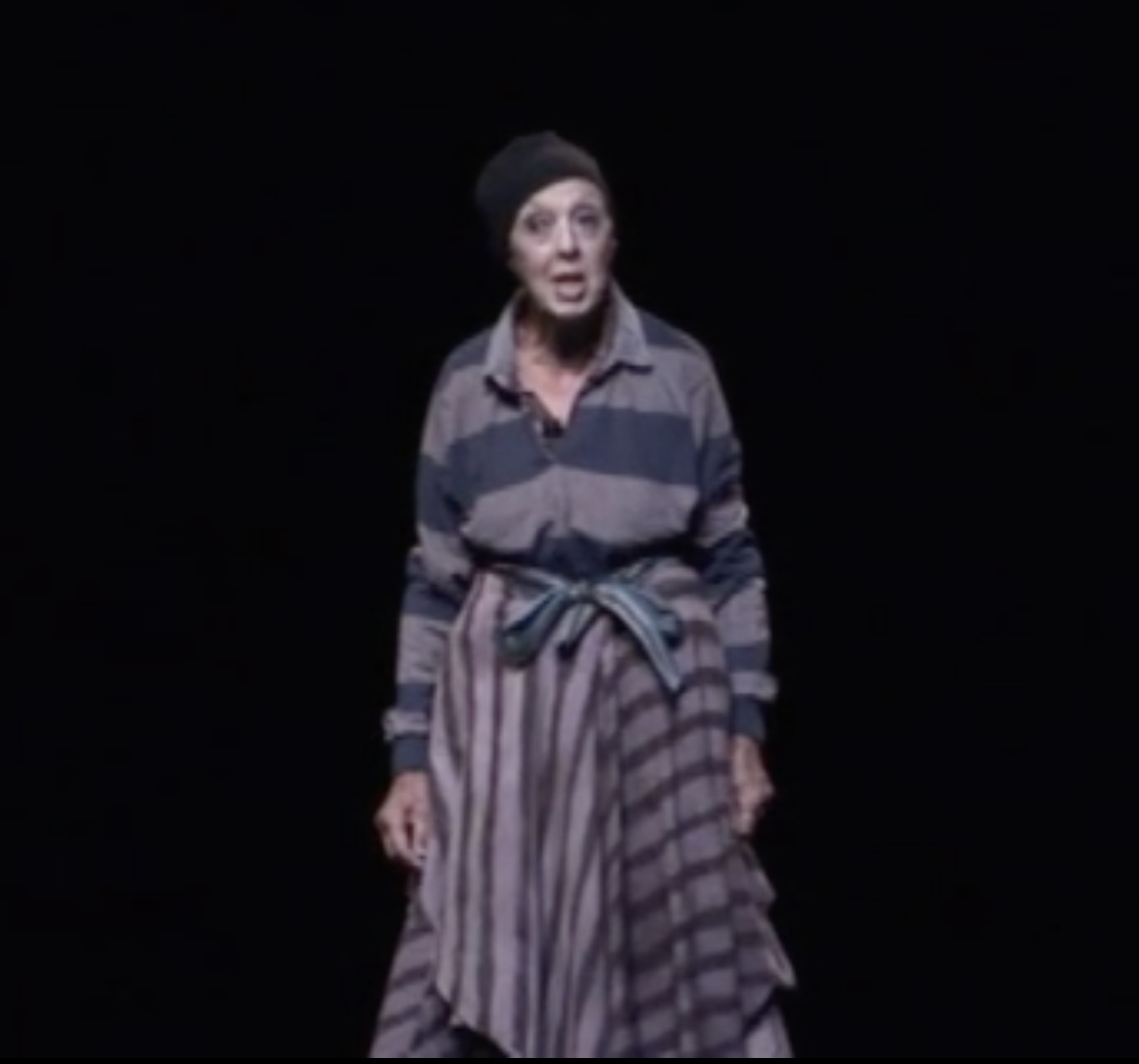

Setterfield as Narrator, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

Gordon takes the lead from the prologue of Henry V in his acknowledgement that the theatre is ill-equipped to represent the epic story of Henry’s war with France. Setterfield tells the audience, “Shakespeare’s Chorus entered and lamented the inadequacies of the stage and urged the audience to use their imagination to compensate for that poor theatre’s deficiencies. But we … being always used to using our imagination, need no such encouragement, so I, as Gordon’s Chorus, will not bother.” Her use of “we” in this passage suggests the distance between audiences of the 16th and 21st centuries in their willingness to suspend disbelief. Yet it also specifically alludes to audiences for dance performances, which demand even more active imaginative engagement from their spectators. Further, by calling herself “Gordon’s Chorus,” she indicates the choreographer’s authorship of the work, displacing Shakespeare as an authorizing agent.

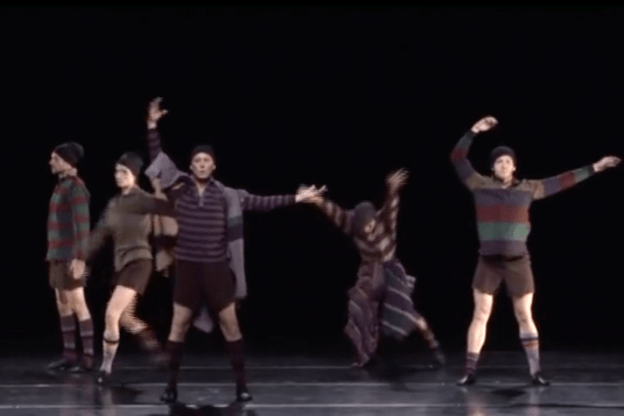

Gordon nonetheless plays a recording of the prologue from Olivier’s film, which accompanies the performers’ opening dance sequence. The movements they perform occasionally relate to the words; for example, when the Chorus describes the “horses … / Printing their proud hoofs i’th’ receiving earth” (Prologue 26-27), the dancers briefly lean over to stamp their feet and slap the floor rhythmically with their hands. Otherwise, however, they make no attempt to “translate” the Chorus’ words into movement. The choreography is distinctive of Gordon’s work in its combination of modern dance technique, pedestrian movements, and some ballet vocabulary. The dancers slide into wide second position pliés, lift their arms out to their sides, then perform a series of turns in attitude, suspend for a moment, and finally walk lightly across the stage, swinging their arms. They change direction as other dancers enter the space, running, sliding, leaping, or falling, and settle in a particular location, bending forward and stretching their arms up behind them, turning in place, or reaching their arms above their heads and slumping down again.

Opening Dance, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

Although almost none of the movement in this opening section relates specifically to Henry V, Dancing Henry Five touches on all of the events of Shakespeare’s play, even if it does not stage them, from the prologue to the final wooing of Henry and Katherine. Gordon’s work is meta-theatrical, continually calling attention to its construction through the Chorus’ narration. Further, although he uses extensive passages from Shakespeare’s play as part of the sound design, he distances the audience from them by cutting, repeating, and overlapping different recordings of the text. As Joyce Morgenroth notes, “Seeing Gordon’s combination of dance, text, and theater, audiences are often unsure what is ad lib, and what is set, what is autobiography and what is artifice. Visual and verbal double entendres create multiple layers of uncertain meaning” (41). Throughout, the choreography presents a mélange of movement that sometimes seems directly related to the play and its characters, and at other times works against the grain of the text, asking the audience to focus not only on the narrative, but also on the movement itself.

The most striking example of meta-theatricality in Dancing Henry Five occurs in the middle of the piece, between Katherine’s English lesson and the Battle of Agincourt, when the Chorus intervenes to let the audience know which parts of Shakespeare’s play have been cut. Setterfield tells the audience, quite nonchalantly, that “we’ve omitted the battle of Harfleur … and we’ve cut the three traitors that Henry condemned, and all of Henry’s old roustabout friends, who after Falstaff’s death join the army.” She indicates that this is due to lack of personnel, but also because they will focus most of their energy on Agincourt, “which is musically much longer.” Walton’s score provides more music for Agincourt than for any of the other scenes that were cut, and will provide a more extended opportunity for choreography than other scenes in Shakespeare’s play or Olivier’s film adaptation.

The Agincourt sequence itself is necessarily expressionistic in its movement and conception. The dancers bring in folding chairs 4 and stand on top of them for the St. Crispian’s Day speech, which is performed in audio by both Olivier and Christopher Plummer. As the speech plays, the dancers move in unison atop their chairs, raising and lowering their arms and legs in a kind of tiptoeing motion. Some of their movements relate to the words: they unfurl their sleeves on “strip his sleeve and show his scars,” touch their mouths on “familiar in his mouth as household words,” and mime placing their hand on the head of a child on “the good man teach his son” (4.3.47, 52, 56). The two versions of the speech overlap and repeat each other, with the climax played several times, undoing the speech’s momentum and undercutting the investment in the triumphal feeling of the text. The dancers leap down from their chairs and bring on long wooden sticks for the battle. Rather than enacting any kind of fighting movements, the dancers bang their sticks rhythmically on the ground, falling into ranks behind Henry, lunging forward while raising their sticks, and performing deep second position pliés, as in the opening scene. They hurl the dummies around the stage, put them in folding chairs and carry them around, and finally all collapse onto the floor, momentarily still. There is no attempt to recreate the sense of a literal battle, and the climactic nature of the scene is undercut by the strategies Gordon uses to defamiliarize Shakespeare’s play through movement.

St. Crispian’s Day, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

Just as Gordon’s staging of the St. Crispian’s Day speech and the Battle of Agincourt distance the audience from the impact of these events, Setterfield’s embodiment of Falstaff earlier in the piece likewise undercuts the possibilities for emotional engagement. As in Shakespeare’s play, Gordon references the death of Falstaff and provides some background from 2 Henry IV to contextualize the character for the audience. Once the former Prince Hal has been “newly crowned King Henry Five,” Setterfield becomes “old, fat, dying Falstaff” by taking off her cap to reveal her white hair, clutching a pillow to her abdomen, and lying down on a gurney. Her manner throughout emphasizes performativity, as there is no attempt to realistically transform her into the old male knight. Further, once the recorded dialogue of Falstaff and Henry from the end of 2 Henry IV has finished playing, she sits up quickly, deliberately breaking the mood, and throwing off her role along with the blanket that covered her. “Okay. Falstaff is dead,” she announces abruptly and unsentimentally, provoking some slight audience laughter at the juxtaposition of the serious scene with the evident need to move the action along expeditiously.

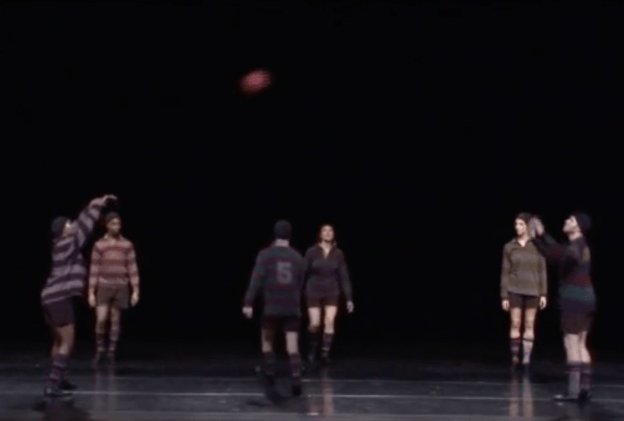

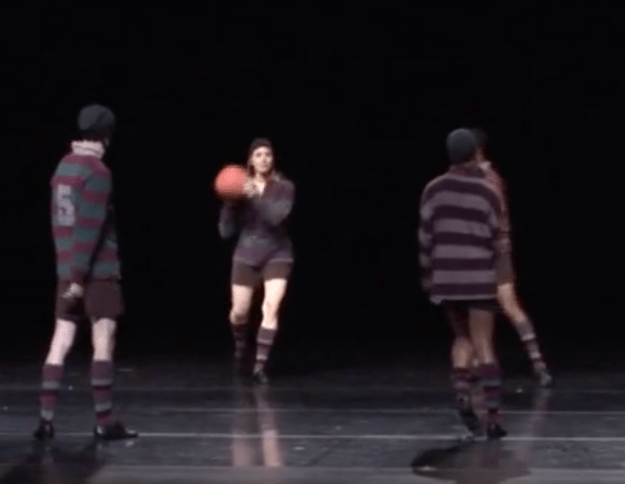

In a later scene, Gordon takes inspiration from the “tennis balls” sent by the Dauphin as an insult to Henry (1.2.258) to stage a dance in which all seven dancers throw big rubber balls 5 back and forth to the strains of Walton’s cheerful Baroque-style music, primarily composed of a harpsichord and an oboe. They bounce and throw the balls, moving continually around the stage, and the game/dance is very inclusive and decorous, rather than competitive. Their movements are mostly pedestrian, primarily walking, rather than dancing, and the throwing and catching of the balls looks almost improvised and random, rather than a set piece of choreography. Banes’ description of Gordon’s work feels appropriate to capture the feeling created by this scene: “he uses movements that look more like behavior than choreography … In every Gordon dance I’ve seen, the movements are specific and deliberate, yet performed with a casual demeanor that nearly belies their careful design” (Terpsichore 105). The rubber ball dance beautifully captures the collision between casual, everyday behavior and deliberate, patterned designs created by the movements of bodies and balls around the stage. Further, Gordon’s choice of words to introduce the scene – “a short court rubber ball dance, after which King Henry Five declares war on France” – plays with multiple meanings and images simultaneously. The “court” references both the royal setting of the story and the decorous music, but also the sports court, on which ball games are played. The “ball” is both the literal rubber balls and a reference to a courtly dance, which will be echoed later in the choreographed wooing between Henry and Katherine. Finally, the use of rhymes in the Chorus’ speech – short/court, dance/France – creates an ironic allusion to Shakespeare’s rhyming verse, particularly the use of couplets to transition from one scene to another. The absurdity of a courtly dance performed with bouncing rubber balls is part of the point here, as is the Chorus’ deliberately amateurish rhyming verse. Gordon is calling attention to the construction of his own work, undercutting the audience’s investment in the progression of events, and creating an ironic and distancing effect from Shakespeare’s play.

Rubber Ball Dance, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

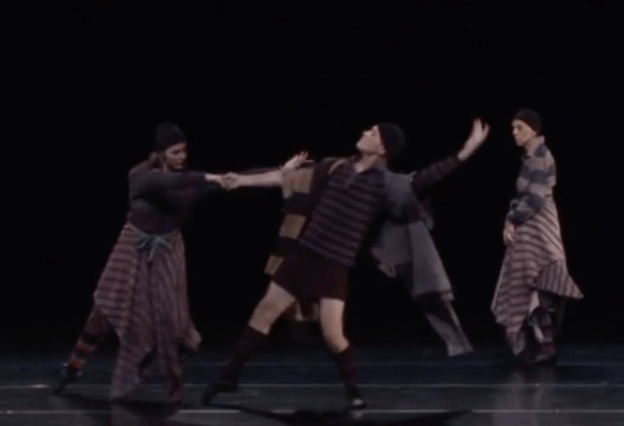

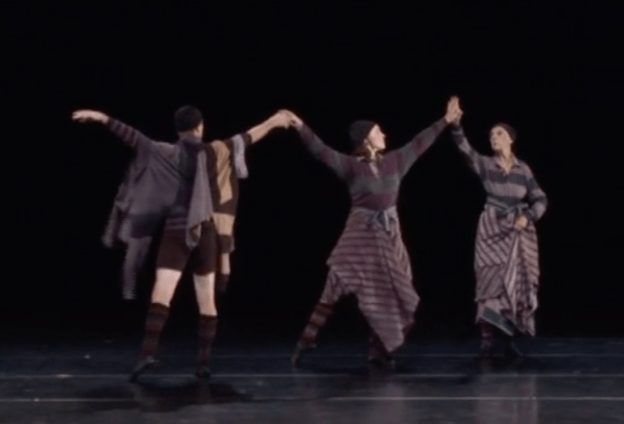

The rubber ball dance also undermines the declaration of war that follows, as well as the associations developed in Shakespeare’s history plays “between dancing and bloody warfare,” as Alan Brissenden notes (18). Further, Gordon’s dance work also refuses to reflect the alternate imagery that Shakespeare creates in the histories contrasting warlike masculinity with “the picture of the soft courtly life of uncaring pleasure, the ‘silken dalliance’ the chorus tells us is left lying in the wardrobe while the youth of England goes to battle” (Brissenden 28). Henry Five, danced by Robert La Fosse in Gordon’s piece, is neither a soft courtier nor a “plain-speaking down-to-earth soldier incapable of the wooing niceties of the courtly lover” (Brissenden 31). His pas de deux with Karen Graham’s Katherine in the final scene does not follow the gendered conventions of Shakespeare’s text or of the pas de deux form itself. The costume design undercuts the gender distinctions between the two, since they both wear the same black skullcap, knee socks, and sneakers. There is also a sense of mutuality in the movement, since they often join hands and move in unison, side by side. Occasionally Henry supports Katherine briefly as she performs a pirouette turn, but otherwise their dancing is mutually supportive. Setterfield is also present, fulfilling the role of Alice in this scene, and at times participates in their dance, turning it into a pas de trois. Her immediate transition back to the role of Chorus at the end of the scene again highlights the meta-theatrical nature of Gordon’s work, never allowing the audience to become too deeply immersed in any individual scene or associate a performer with a single character.

Pas de deux and Pas de trois, Dancing Henry Five, Montclair State University, 2011

Brissenden notes that Shakespeare’s history plays do not tend to incorporate dance as part of the action, since their primary concern is with “war and disorder.” However, “dancing is mentioned more often [in Henry V] than in any of the others,” perhaps because it “concludes with a marriage and the prophecy of a birth and political harmony (however temporary that harmony was to prove)” (33). Perhaps in this light “dancing Henry Five” is not such a preposterous idea after all. Gordon does not, however, attempt to render a “translation” of Shakespeare’s history play into dance; rather, his piece defamiliarizes Henry V, providing us with a strange new vision of the story rooted in the movements of the dancing body.

© Elizabeth Klett, 2023.

Notes

Text | Notes | Works Cited | Cite | Related Content

- Walton collaborated with Olivier on all three of his Shakespeare films: Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and Richard III (1955). As James Brooks Kuykendall notes, “these scores were composed at the height of his career” (10), and he had a significant influence on the finished films. Kuykendall’s article analyzes the extant scores and manuscripts to note the extent of Walton’s detailed involvement in scoring these films. ↩︎

- In Setterfield’s April 2023 obituary, dance critic Alastair Macaulay called her Gordon’s “muse” and noted that the couple “were once called ‘the Barrymores of postmodern dance.’” Gordon pre-deceased Setterfield in January 2022; in his obituary in The New York Times, Gia Kourlas wrote that “he was part of a generation who broke the rules about what a dance could be.” ↩︎

- Writing in 2022, dance critic Wendy Perron notes that “We look back today and see that Judson was the crucible for postmodern dance, Contact Improvisation, and a new way to look at dance/art collaborations. The influence of Judson is so pervasive that it affected almost everyone in the downtown scene, and it’s rippled outward nationally and internationally.” ↩︎

- Folding chairs are a signature prop associated with Gordon’s choreography, particularly recalling his Chair, Alternatives 1 through 5 (1974), which he and Setterfield performed as a duet: “sitting on [the chair], kneeling on it, lying on it, falling off it, folding it, pulling it over the body, leaning in it, stepping on, over, or through it” (Banes, Terpsichore 103). ↩︎

- I suspect the rubber balls in Dancing Henry Five are also a tongue-in-cheek reference to Gordon’s Mama Goes Where Papa Goes (1960), a duet for himself and Setterfield which opened “with Gordon standing on stage, his arms full of rubber balls. He opened his arms, dropped all the balls, and when they had stopped bouncing and rolling away, he walked off” (Banes, Terpsichore 99). ↩︎

Works Cited

Text | Notes | Works Cited | Cite | Related Content

Banes, Sally. Reinventing Dance in the 1960s: Everything Was Possible. U of Wisconsin P, 2003.

_____. Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance. Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

Brissenden, Alan. Shakespeare and the Dance. Humanities Press, 1981.

Gordon, David. Dancing Henry Five. Performed at Montclair University as part of Peak Performances, 2011. https://vimeo.com/45450765

Kaufman, Sarah. “Positions of Power.” Washington Post, May 14, 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/05/13/AR2007051301273.html

Kolb, Alexandra. Performing Femininity: Dance and Literature in German Modernism. Peter Lang, 2009.

Kourlas, Gia. “David Gordon, a Wizard of Movement and Words, Dies at 85.” New York Times, February 4, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/04/arts/dance/david-gordon-dead.html

Kowal, Rebekah J. How to Do Things With Dance: Performing Change in Postwar America. Wesleyan UP, 2010.

Kuykendall, James Brooks. “William Walton’s Film Scores: New Evidence in the Autograph Manuscripts.” Notes vol. 68, 2011, pp. 9-32.

Macaulay, Alastair. “Valda Setterfield Dies at 88; a Star in the Postmodern Dance Firmament.” New York Times, April 24, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/21/arts/dance/valda-setterfield-dead.html

Morgenroth, Joyce. Speaking of Dance: Twelve Contemporary Choreographers on Their Craft. Routledge, 2004.

Morris, Gay. Moving Words: Re-writing Dance. Routledge, 1996.

Perron, Wendy. “What Was Judson Dance Theater, Who Was Against It, and Did it Ever End?” June 14, 2022. https://wendyperron.com/judson_dance_theater/

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. The Norton Shakespeare, 2nd edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt. Norton, 2008.

Citation

Text | Notes | Works Cited | Cite | Related Content

Klett, Elizabeth. “Defamiliarizing Shakespeare in David Gordon’s Dancing Henry Five.” The Shakespeare and Dance Project, edited by Linda McJannet and Emily Winerock, August 4, 2023. https://shakespeareandance.com/articles/defamiliarizing-shakespeare-in-dancing-henry-five/. Accessed [date].

Related Content

Text | Notes | Works Cited | Cite | Related Content

The full performance of David Gordon’s Dancing Henry Five at Montclair State University (2011) is available free of charge on Vimeo (1 hour):

Updated August 4, 2023.

2013-2026. All rights reserved. The Shakespeare and Dance Project.