Some Challenges in Staging Dance in Shakespeare’s Plays

by Nona Monahin

Note

This paper focuses on staging dance in two of Shakespeare’s plays: Romeo and Juliet and Much Ado about Nothing.

It was presented at the 5th Historical Dance Symposium, Burg Rothenfels am Main, Germany, and was published in the symposium proceedings as:

Nona Monahin. “Negotiating Text and Movement: Some Challenges in Staging Dance in Shakespeare’s Plays.” In The Ball: Pleasure, Power, Politics, 1600–1900. 5th Historical Dance Symposium, Burg Rothenfels am Main, 15-19 June, 2022, Germany. Conference Proceedings, edited by Uwe Schlottermüller and Howard Weiner, June 2022.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Source Texts

- Terminology

- The Practice of Impromptu Masking

- Dance Sources

- Romeo and Juliet

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Concluding Remarks

- Accompanying Images

- Endnotes

- Cite

Introduction

The plays of William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) contain numerous references to dance, some of which are used to create wordplay, others to illuminate a particular character or dramatic situation.[1] Dancing also occurs as part of the action of many plays, although Shakespeare does not name specific dances in such situations. One challenge to choreographers and directors who wish to use period dancing is to find, or create, appropriate dances, and to integrate them into the dialogue and action. Another challenge, regardless of whether the staging is in period style or is updated, is to make the dance references intelligible to today’s audiences.

In this paper I examine the dance scenes in two of Shakespeare’s plays, Romeo and Juliet and Much Ado About Nothing (henceforth Much Ado), in order to illustrate such challenges and discuss possible solutions. The dance scene in Romeo and Juliet has been likened to a film scenario, with constant alternations between what in film terminology may be called close-ups and long shots.[2] Put simply, much is happening — different characters conversing, issuing orders, arguing, thinking aloud, running around, playing musical instruments, dancing — and much of it is happening simultaneously. To integrate all these elements into an organic, seamless whole presents a challenge to the director and choreographer. Additionally, because this scene is lengthy, one needs to decide whether to use one dance or several.

The staging of Much Ado presents additional challenges. The main dance scene is preceded by a brief passage in which one of the characters comments on several dances. Regardless of whether any of these were intended to appear in the ensuing dance scene, the textual references deserve to be understood, at the very least by the director, choreographer, and the actors, but hopefully also by the audience.

I should emphasize that my aim in this paper is not to explore how such dance scenes might have been performed in Shakespeare’s time, but to establish a practical connection between the known historical information and our own times by examining possible ways of creating historically informed stagings of the dance scenes today. My thinking is informed by practical experience in staging/choreographing these, as well as other, Shakespeare plays, but my suggestions are not intended to be prescriptive. If I appear to conflate the roles of choreographer and director, it is because in the scenes under consideration it is impossible to separate the two. The director and choreographer need to work together to shape the whole scene, in which the dances are integrated rather than simply added. When I choreographed these dances for the Hampshire Shakespeare Company in Massachusetts, I was fortunate to work with directors (Timothy Holcomb for Romeo and Juliet and Benjamin Ware for Much Ado) who welcomed such close collaboration.[3]

Source Texts

Shakespeare’s plays were originally printed in quarto and folio formats. The “First Folio” was printed in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, and is the most comprehensive of the early editions, containing thirty-six plays, some of which had not appeared previously in print.[4] The quartos were single-play prints that appeared during Shakespeare’s lifetime. Some plays appeared in more than one quarto edition, and some of these may have been records of performances. An abridged version of Romeo and Juliet first appeared as a quarto in 1597, but the more comprehensive second quarto of 1599 is used as the basis for many modern editions.[5] Much Ado appeared as a quarto in 1600, and was included with little change in the First Folio.[6]

These early editions contain very few stage directions and do not divide the acts into scenes the way modern editions do. This paucity of staging guidelines has prompted many editors, over the centuries, to add their own stage directions and scene divisions, to assist readers and theater practitioners.[7] Although admirable in principle, this practice, unless clearly annotated, can result in obfuscation. Because I wanted to work with texts that were free from subjective interpretations, I have used the text from the second quarto (henceforth Q2) for Romeo and Juliet, and the First Folio (henceforth F1) for Much Ado, noting any changes in the alternative editions, and modernizing some of the spelling and punctuation.[8] The Hampshire Shakespeare Company productions, to which I refer below, used F1 as their main source.

Terminology

Although when discussing the dance scenes in Romeo and Juliet and Much Ado today, it is common to use terms such as “ball,” “ball scene,” and “ballroom,” in Shakespeare’s England such episodes of social dancing would have been referred to as “revels” or simply as “dancing.” The terms “masks” or “masques,” in addition to denoting the elaborately structured and rehearsed court productions, could also be applied to the more informal types of dance events found in Romeo and Juliet and Much Ado. (Romeo, for instance, uses “mask” to refer to the event he and his friends are planning to attend).[9] Regarding the two spellings, Janette Dillon has written that although these suggest different theatrical forms, there was actually no distinction between the terms “mask” and “masque” in practice, and Emily Winerock has noted that “in England prior to the 1580s, the term mask referred to an activity, not to an item worn.”[10] The face coverings worn by men were known as “visors,” “vizards,” or variations on these words, with “mask” gradually becoming used to refer to face coverings worn by women.[11] The disguised young men who would “crash” parties (see below) were known as maskers, masquers or revelers. Shakespeare used the terms interchangeably in the First Folio edition of Much Ado, where one character announces that “the revelers are entering,” while the stage directions read “Enter. . . maskers with a drum.”[12]

The practice of impromptu masking

In both plays under discussion the dancing begins with the arrival of men in disguise, with their faces hidden by visors. The tradition, especially during festive times, of groups of young men in disguise, some of them carrying torches to light the way, processing through the streets, knocking on doors where a party was in progress, and requesting admittance, was widespread in both England and on the Continent, and went through many permutations depending on time and place. There were periods when such activities were forbidden in England, and the sale of masks was illegal.[13] This was likely partly due to risks associated with allowing unknown visitors to enter one’s home and is reflected in Romeo and Juliet when such an intrusion provokes Tybalt’s anger (although in this case Tybalt is incensed because he actually recognizes the intruder as belonging to a rival faction). It was customary for such visitors to make an offering to the hosts, such as a recitation, or a dance number, after which the hosts would invite them to dance with the assembled guests.[14] Often the dancing was the result of the maskers’ visit. This is the case in Romeo and Juliet where, after the maskers arrive, tables need to be moved to make room for the dancing. Emily Winerock has written about this scene:

This flurry of activity indicates . . . that the dancing that is about to occur is happening because of their [the masquers’] arrival. There were musicians on hand, but the dancing that we see in this scene is unscheduled, improvised, and a direct response to the sudden arrival of mysterious young men in masks.[15]

This certainly differs from the practice seen in many modern productions, and especially in films, where Romeo and his friends arrive at a sumptuous ball that is already in progress.

In Much Ado the dancing also begins with the arrival of the maskers, but here the revels are planned rather than spontaneous.

Dance sources

Although Shakespeare’s dance directions do not go beyond such phrases as “Music plays and they dance,” his textual references reveal the large variety of dances with which he was familiar. Altogether, his plays mention seventeen dances or dance figures, some courtly, some popular, and a few exotic or elusive. Of these, contemporary choreographies (either English or continental) are extant for the following dances: measures (which include almains and pavins), cinquepace and galliard, coranto, branles (“French brawls”), volta (“lavolta”), canary, and “passy measures pavin.” Partial choreographies give us some information about the morris and the mattachins, and several dances include a “hay” figure. Choreographies for “country dances” become available after the mid-17th century, in the publications by Playford.[16] There are no reliable choreographies for a jig, roundel, carole, bergomask, or the “bacchanals.”[17]

The majority of the extant choreographies are from Italy and France. From England, apart from the later books of country dances, there are several so-called “Inns of Court” manuscripts (dating from the mid sixteenth to the late seventeenth centuries) that provide instructions (albeit very abbreviated ones) for many English measures.[18] The Inns of Court manuscripts additionally mention several other dances that were commonly danced after the measures had concluded. These include the cinquepace, galliard, coranto, volta, and “French brawles” — dances that are mentioned by Shakespeare, and for which choreographies exist in a French source, the well-known Orchésographie by Thoinot Arbeau (1589).[19] Although transferring choreographies across national borders is potentially problematic, there is evidence that dances and dancing styles of the elite traveled widely, and eyewitness accounts confirm the performing of “foreign” dances at various European courts.[20] It seems reasonable to resort to the non-British sources, as long as one does so thoughtfully, examining each situation on a case-by-case basis.

Romeo and Juliet

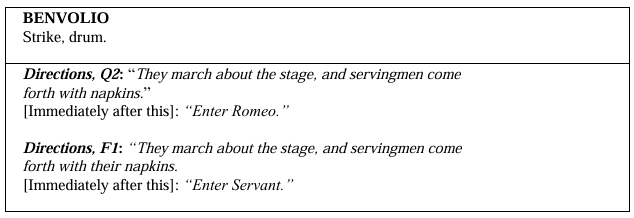

In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the dance scene occurs in what modern editions usually designate as Act 1, scene 5. In the preceding scenes Romeo was being coaxed by his friends, Benvolio and Mercutio, to accompany them to the Capulet banquet. The fact that Romeo is from the rival family of the Montagues does not pose a serious problem since the young men will be in disguise, with their faces covered by visors. However, Romeo is despondent because he has been rejected by Rosaline, the young lady whom he professes to love, although Benvolio has promised to show him many superior beauties who will be at the feast besides her. Romeo reluctantly agrees to go but is adamant that he will not participate in the dancing. Instead, as he reiterates many times, he will go as a torchbearer.[21] He also has a premonition that the night will end badly. Nevertheless, he gives in: “On, lusty gentlemen,” after which Benvolio gives the direction to “Strike, drum!”

Although there were no scene breaks in either the quarto or folio editions, modern editions that add scene breaks divide the stage directions so that “They march about the stage” comes at the end of “scene 4,” immediately following Benvolio’s “Strike, drum,” while “Servingmen come forth with napkins” marks the beginning of “scene 5.” If one eliminates this break, it is possible to see the two activities as taking place simultaneously.[22]

The servants now have eleven lines of dialogue which revolves around the chores they are performing in clearing up after the feast. The main servant (whose entry is indicated in F1 by “Enter Servant,” corrected from “enter Romeo” in Q2) gives orders to the other three, including notice that they are wanted “in the great chamber.”[25]

Some scholars have pointed out that the direction to “march about the stage” could be used to indicate that the action was moving from one location to another.[26] In this case the revelers are coming in from the street. The inclusion of the brief servants’ interlude may be there to indicate that the new location is indoors. In fact, the main servant’s remark about “the great chamber” (noted above) could suggest a second indoor location. Thus, during this short transitional episode, the revelers would appear to pass from the street, through an unidentified part of the house, to the “great chamber” where, presumably, the festivities are taking place.

There are a number of things to consider here. First, how many maskers are there? The F1 directions at the beginning of the previous “scene,” when the youths were just setting out for the night, read: “Enter Romeo, Mercutio, Benvolio, with five or six other maskers, torch-bearers.”[27] Although the numbers are only suggestions, and such directions tend to vary between the quartos, as they no doubt varied between performances, one would presume that more people than just the three friends enter the Capulet house, making a procession here entirely plausible.

Second, if the events are simultaneous, the drum would need to be subdued so as not to drown the servants’ dialogue. But then, such a waning and waxing in volume may in fact be an appropriate way to indicate changes in location. Third, given that it was customary for arriving maskers to present either a speech, or a dance, or both, for their hosts before being invited to dance with the guests, could this marching morph into a such a presentation dance? Could it perhaps continue for a short while after the servants have left and while Capulet and his guests are moving towards the revelers? Tudor masques certainly influenced the early plays of Shakespeare,[28] and Anne Daye has observed that “Tudor masques were processional in concept, with the marching entry as the defining feature.”[29] (In Much Ado, to be examined below, the maskers also enter “with a drum,” which suggests a marching procession). Earlier in Romeo and Juliet the youths had discussed the possibility of presenting a speech to their hosts but decided to simply “measure them a measure and be gone.”[30] Is this marching meant to be that “measure?” [31]

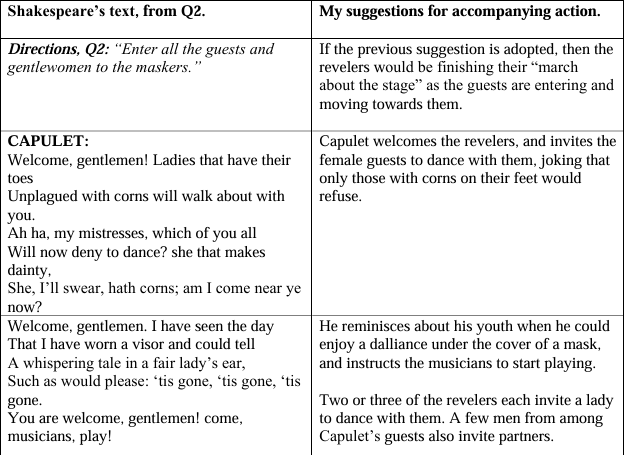

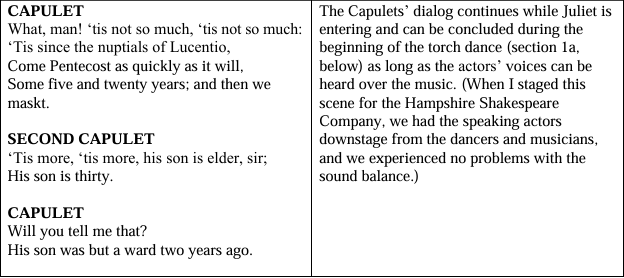

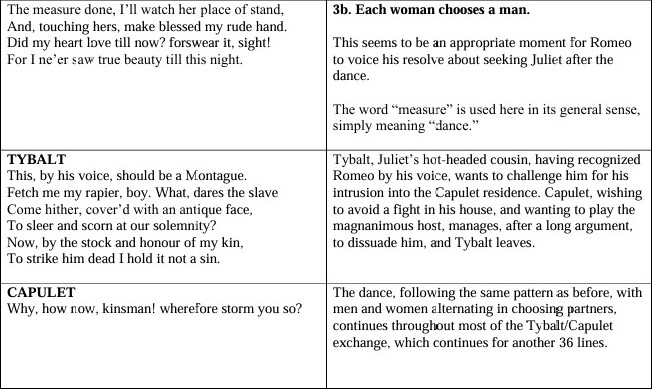

The servants’ episode ends with the direction “Exeunt” in Q2 (none in F1), after which the Capulets and their guests approach the revelers. The chart below is partly based on my staging of this scene for the Hampshire Shakespeare Company.

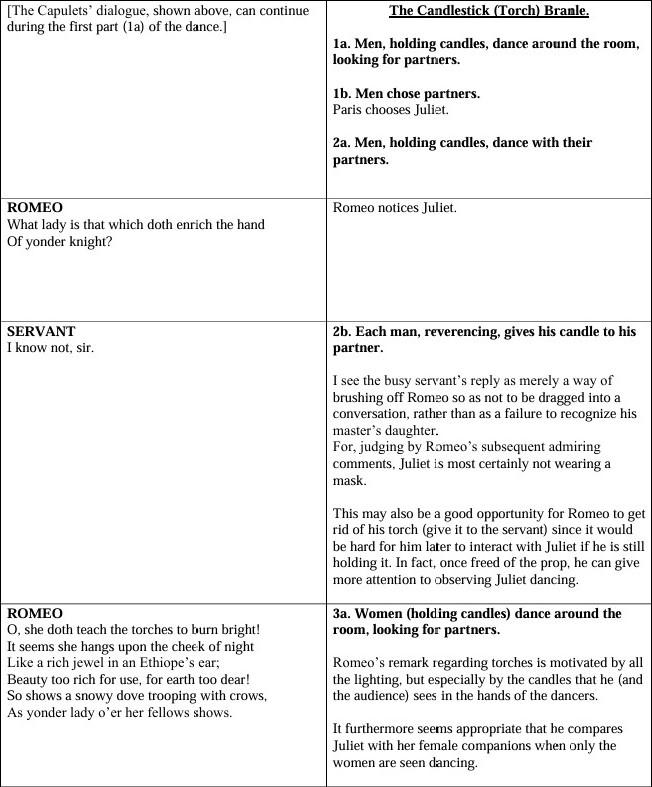

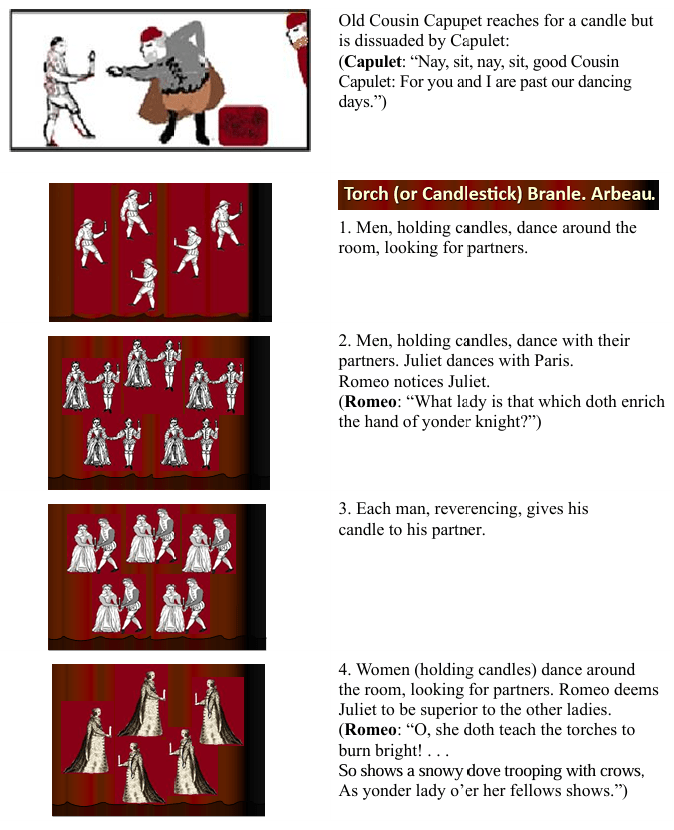

We now come to the question of the choice of dance. For the Hampshire Shakespeare production, I chose the “Candlestick Branle,” also called “Torch Branle” (“Branle du chandelier” “aultrement appellé le branle de la torche”) described by Thoinot Arbeau in his Orchésographie of 1589.[35] Although it is called a “branle,” this almost seems to be a misnomer, for, unlike any other branle in Arbeau, it uses “allemande” steps (three steps forward on three counts, and a follow-through, forward, of the trailing foot, on the fourth count). In that sense it is closer to a “measure,” although my choice was not necessarily prompted by Romeo’s remark (“the measure done”), since in Shakespeare’s time “measure” could be used as a general word simply to mean “dance.”[36] A torch dance is also suggested by Alan Brissenden, who cites a reference to a such a dance in Arthur Brookes’ version of the story that served as a source for Shakespeare’s play.[37] Even so, a torch dance is not necessarily the obvious choice for this scene.[38] However, I thought it would add a touch of irony if Romeo, having insisted on a torch-bearing rather than a dancing role, should then fall in love with a girl who is doing a torch dance.

Furthermore, it is obvious that torches are on Romeo’s mind, and that his reflection that Juliet “doth teach the torches to burn bright” is prompted by the illumination of the room, which must be quite intense since Capulet had just ordered the servants to augment it. The audience knows this too, but it is important that they see and experience it as well. It is easy enough to create the appropriate ambience in a film, or a stage production that can employ sophisticated lighting. Our production, on the other hand, used a small, semi-portable set, and was held outdoors, in daylight, so that it was not possible to achieve the ideal level of illumination by means of stage lighting alone. Having candles in the hands of the dancers, making the candles, through their exchanging between partners, be a part of the dance, as it were, seemed an effective solution. This way, even if the handheld candles did not intensify the general lighting, they were at least more conspicuous. Below I delineate how I matched the different sections of the “Torch Branle” with the concurrent dialogue and action.

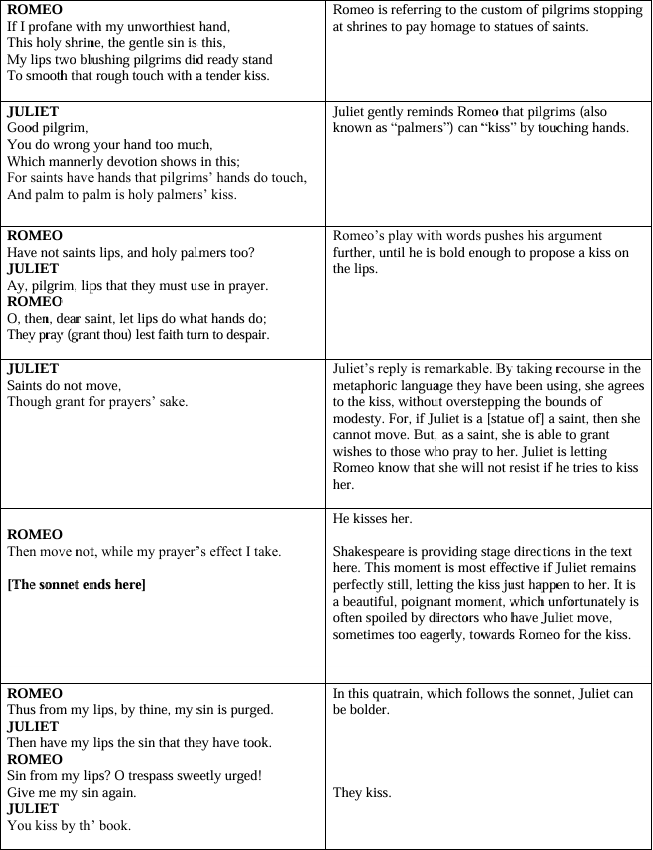

Romeo can finally approach and interact with Juliet in the famous sonnet. Shakespeare has Romeo and Juliet gently match wits in an exchange based on metaphors that take as their starting point the custom of pilgrims stopping at shrines to pay homage to statues of saints.

Because this is such a poignant moment in the play, the question arises of how to stage this scene. Whatever happens in the background, it should not detract from the main focus. Should the other characters remain motionless until the young couple stops speaking? Should they go about their business silently, like in a scene from a movie with the sound turned off? Should they continue with the “Torch Branle” (in which case Romeo’s earlier remark about waiting until the measure is finished could reasonably be interpreted as referring to a section of the dance). Or should they do a different dance?

The first two options seem too modern to me. The last option, because it involves a new dance, risks drawing attention to that dance and away from the couple.[41] In the Hampshire Shakespeare production we continued with the torch dance. The director remarked (perhaps partly in jest) that he purposely wanted the dance to start to feel boring, so that the audience would ignore it and focus instead on the couple speaking. I think if I were staging this scene today, I would keep the torch dance throughout, but include variations in the music (and perhaps in the choreography too) and make the variation just before Juliet’s exit have a touch of finality about it, making it an appropriate place to leave the dance for those who wish to do so, but then immediately starting up the tune again from the beginning.

The dance could end about here. In the final moments of this scene Juliet’s nurse calls to her, Romeo and Juliet each (separately) question the nurse, and each learns, to their dismay, the identity of the other. Immediately after this Benvolio and Mercutio, fearing that trouble may be brewing, hasten to make Romeo come away with them. Capulet tries to persuade them to stay to supper, but after they whisper something in his ear (this stage direction is present only in Q1, supposedly a performing copy) he accepts their explanation and bids them farewell, commenting on his own tiredness and his desire to retire for the night, and thus ending the party.[43]

Much Ado About Nothing

In this comedy, a young couple’s betrothal is threatened by malicious slander. However, after much confusion, the heinous plot is thwarted, and, with the help of some devious matchmaking, the play culminates in not just one, but two, marriages. The play also involves two dance scenes, the second of which celebrates the double wedding at the end of the play. The first one involves masked revelers, but, unlike the situation in Romeo and Juliet, here the revels are planned, and the revelers are expected. This dance scene is preceded by a commentary on three different dance types. Whether or not any of these dances were meant to appear in the ensuing revels is not known, but an attempt to make the dance references intelligible to today’s audiences can be made.

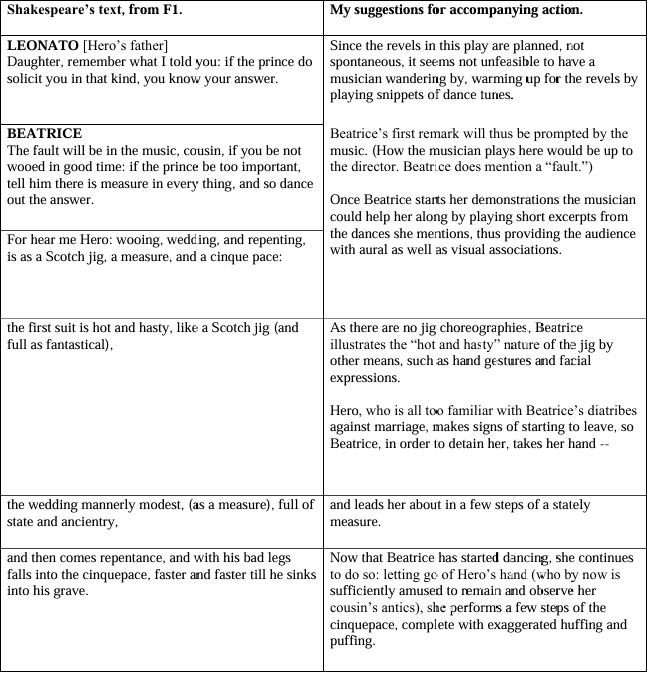

In what most modern editions of Much Ado designate as Act II, scene I, Beatrice, a young lady who despises the idea of marriage, is giving advice to her artless cousin Hero, who is expecting a marriage proposal.

BEATRICE

The fault will be in the music, cousin, if you be not wooed in good time. If the Prince be too important, tell him there is measure in every thing, and so dance out the answer. For hear me, Hero: wooing, wedding, and repenting, is as a Scotch jig, a measure, and a cinquepace; the first suit is hot and hasty like a Scotch jig (and full as fantastical), the wedding, mannerly modest (as a measure), full of state and ancientry; and then comes repentance, and with his bad legs falls into the cinquepace faster and faster, till he sinks into his grave.[44]

Although there are no extant choreographies for a jig as a dance from this period, there are plenty of incomplete descriptions that point to its boisterous, unruly nature. In other words, it is an apt image for the fervid and impulsive courtship phase of a relationship. The likening of the wedding ceremony to a stately measure is self-evident. It is the third phase, repentance, or regret, that according to Beatrice inevitably follows the marriage, that has elicited the largest number of interpretations, most of which are plausible, to some extent, but many of which also, to some extent, miss the mark. Many scholars have acknowledged the strenuous and tiring nature of the cinquepace, with its continual hopping, kicking, and jumping, and some have associated it, in the present context, with the male dancer, and therefore, with the husband in a marriage. But although the image of a man struggling to dance “with his bad legs” is a striking one, the “he” in Beatrice’s comment refers to “repentance” rather than to the husband. He, that is, repentance, can afflict both partners in the marriage. I believe that Beatrice’s chief aim here is to stress the inevitability of marriage leading to regret, just as it is inevitable that the measure will be followed by the cinquepace. Although Beatrice is generalizing for the sake of getting her point across, it is true that in numerous English sources the fairly sedate dances known as measures are followed by the lively cinquepace, or by its fancier version, the galliard.[45]

The question is, is it possible to make these references intelligible to today’s audiences without relying on program notes? Although it would indeed be hard to illustrate the inevitability of the one dance following the other, this relationship is implied in Beatrice’s line “and then comes repentance” (my emphases). Perhaps the best solution would be to acquaint the audience with the nature of these two dances, and then present them more than once in the same order, in the hope that the associations will register.

To achieve this, one could supplement Beatrice’s speech with demonstrations of dance steps, making sure to integrate such movements so they do not resemble gratuitous miming actions as in a children’s nursery rhyme. Additionally, if repetition is a key to memory, one could perform the same dances in the ensuing dance scene, separated from Beatrice’s speech by only four lines of dialogue. Moreover, Beatrice’s reference to music, at the start of her advice to Hero, could be put to good use, to help strengthen the associations by aural means. The chart below is partly based on my staging of this scene for the Hampshire Shakespeare Company.

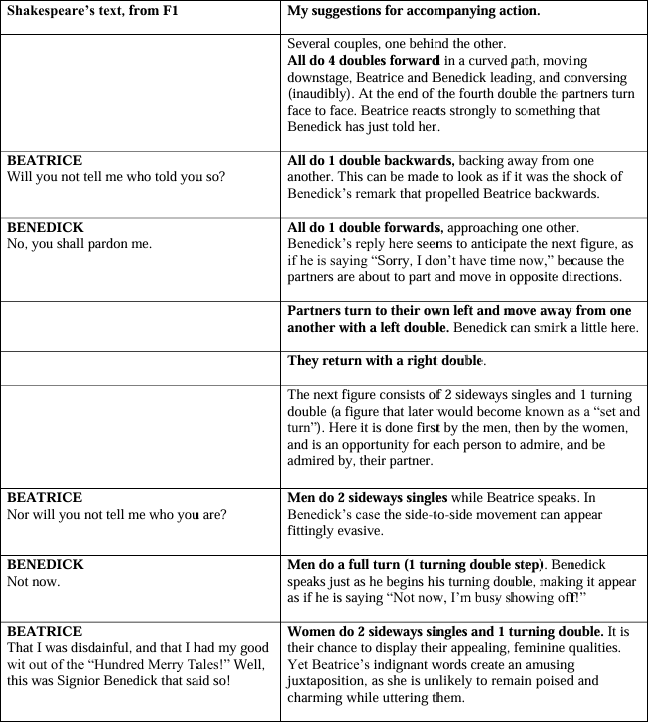

Four lines later, the revels, featuring four couples conversing and dancing, begin. I will not discuss the entire passage here since I have written about it elsewhere, and since the staging problems are not dissimilar to those encountered in working with Romeo and Juliet.[47] Instead, I will remark briefly on the first couple to speak, Hero and the Prince (Don Pedro), and then focus on the interactions between the last couple, Beatrice and Benedick.

For this scene, instead of using just one dance, I chose several measures to be danced in succession. Several of the conversations revolve around the idea of hidden identity, not surprising since the men’s faces are covered by visors, and also in keeping with the theme of the play (the “about nothing” in the title can suggest “about noting,” as has often been pointed out.) Each couple’s dancing style would be affected to some extent by their personality and by their dialogue, which raises the question of why the conversation of the first couple to speak appears somewhat out of character. Hero’s replies to the Prince seem much too cheeky, more like something one would expect from her cousin Beatrice. However, this does not have to conflict with Hero’s demure disposition, or affect her dancing style, since I feel that her somewhat high-spirited responses may be efforts at trying to hide her embarrassment, as at this stage she is under the mistaken impression that the Prince is about to propose to her, when in fact he is wooing on behalf of Claudio, the young man she actually wishes to marry.[48]

Now, on to Beatrice and Benedick. Beatrice had poured out her views on marriage to her cousin in the form of analogies to different dances, and it is now the choreographer’s task to make her remarks and demonstrations carry over from the previous scene into this one. Benedick is the man Beatrice professes to despite, as he does her, although in truth all they need is some assurance about the other’s true feelings in order to turn their opinions around. But during this dance scene that stage is still in the future.

When it was time for Beatrice and Benedick to speak, the dance I chose to accompany them was the “Black Almain,” partly because, of all the extant measures, this one has the most complicated choreography, providing opportunities for errors, intentional or not.[49] The chart below is partly based on my staging of this scene for the Hampshire Shakespeare Company.

After this, as Beatrice and Benedick continue talking, their dancing starts to disintegrate, then stops altogether, while the other couples do their best to ignore the disruptive couple. Finally, the sound of a new dance (a cinquepace) alerts Beatrice that they “must follow the leaders,” which is ironic, since they used to be the leaders. Another reason why I chose the Black Almain is because it is the dance that precedes the cinquepace in several sixteenth-century English sources.[52] Thus “repentance” really does follow Beatrice and Benedick’s measure. This arrangement could also work in a non-period-style production, as long as one chooses two contrasting dances with distinctive music (or possibly a song that has a tranquil opening but later becomes fast and boisterous.)

The cinquepace is not a simple dance, and takes time to learn, something that may not be possible if rehearsal time is limited, or if the actors have little dance experience. Additionally, the floor needs to be suitable (non-resilient surfaces such as concrete are to be avoided when doing hops and jumps). Nevertheless, even if the conditions are not optimal for dancing the cinquepace, it can still be incorporated into this scene. The musicians could play a cinquepace melody (the same one to which Beatrice had earlier demonstrated steps) as everyone starts moving off stage, as if the dancing was progressing to a new location. This transition can be very informal, so that those who can dance the cinquepace do so, while others walk along, maybe throwing in a few dance steps, clapping the rhythm, or indicating with gestures that they are not up to it – anything to draw the audience’s attention to this dance. Because the cinquepace has a very distinctive rhythm, and because the audience had already heard snippets of it during Beatrice’s earlier conversation with Hero, and saw her step demonstrations, they would probably recognize it as the cinquepace/repentance music.

These themes could be echoed in the dancing at the end of the play. For the final dance scene in our production, I chose a circular choreography, to reinforce the (by now) achieved harmony, and one without hops and jumps, so that everyone on stage could participate. The music, however, had a very prominent cinquepace rhythm, as if to ask the question: will the two couples live happily ever after, or will their married bliss contain just a touch of “repentance?”

Concluding remarks

I hope I have shown some of the challenges involved in importing dances from another time period into contemporary theatrical productions. Particularly with an author like Shakespeare, who not only had a knowledge of many dances, but was able to use them in ways that go well beyond mere decoration, there are no short cuts. The text helps to elucidate the dance, and vice versa. It is a pity that a lack of historical information has resulted in some modern directors cutting either Shakespeare’s dance references, or even entire dance scenes. By honoring Shakespeare’s dance language and striving to understand it, directors can uncover and convey complex and rich layers of meaning that can enhance their productions of these plays.

© Nona Monahin, 2022, 2024

Accompanying Images

I incorporated a few drawings from Arbeau’s Orchésographie (1589) and Caroso’s Il Ballarino (1581) into these illustrations.

Endnotes

[1] I wish to thank my husband, Christian Rogowski, for reading this piece and providing helpful feedback. Additionally, enduring thanks are due to John Bell and Anna Volska, since my interest in Shakespeare dates back to a 1975 performance of Much Ado About Nothing by the Nimrod Theatre, in Adelaide, Australia, directed by John Bell, with Anna Volska playing Beatrice. That production, which I saw three times, showed me how it is possible to make the text come alive, so to speak, a principle that I have tried to apply to my stagings of Shakespeare’s dance scenes.

[2] TABI: “Editing Shakespeare” 2003, p. 20, says: “Shakespeare the director organised the ballroom-scene in a cinematic way: totals and close-ups alternate all through the scene.”

[3] Hampshire Shakespeare Company “Shakespeare Under The Stars” 1998 Season: Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Benjamin Ware, performed 23 June to 11 July, 1998, in Amherst, Northampton, and New Salem, Massachusetts. Romeo and Juliet, directed by Timothy Holcomb, performed 16 July to 1 August, 1998, in Amherst, Northampton, and Hadley, Massachusetts. https://hampshireshakespeare.com/

[4] SHAKESPEARE: Mr. William Shakespeare’s comedies, histories, & tragedies [henceforth: Title of play, F1], London 1623

[5] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet [Second Quarto, henceforth Q2], London 1599

[6] SHAKESPEARE: Much Ado About Nothing [First Quarto, henceforth Q1], London 1600

[7] In a fascinating and informative article, TABI: “Editing Shakespeare” 2003, has traced the editing history of Shakespearean works from the 18th century to the present, and presented, as a case study, a detailed comparison of six 20th-century editions of the dance scene in Romeo and Juliet.

[8] I copied the texts from online facsimiles of the quarto and folio editions of these plays held in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., U.S.A. I am grateful to the Folger Library staff for helping me navigate through their vast treasure trove of online resources. https://www.folger.edu

[9] Romeo expresses his hesitancy about going to the Capulet party: “And we mean well in going to this Mask; but tis no wit to go.” SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet 1599 [Q2], leaf C2r.

[10] DILLON: “From Revels to Revelation” 2007, p. 59; WINEROCK: “Licence to Speak” 2021, p. 49

[11] See WINEROCK: “Licence to Speak” 2021, p. 49-51. In the plays under discussion, the women are not wearing masks, as becomes obvious from the dialogue.

[12] SHAKESPEARE: [Much Ado, F1] 1623, leaf I5r., p. 105

[13] See DILLON: “From Revels to Revelation” 2007, p. 62

[14] For the information on masks and masking practices, I relied heavily on two works: WINEROCK: “We’ll Measure Them a Measure” 2017 (in which Winerock also includes a discussion of her staging of the dance scene in Romeo and Juliet), and DILLON: “From Revels to Revelation” 2007

[15] WINEROCK: “We’ll Measure Them a Measure” 2017, p. 5

[16] In The Tempest, for example, Shakespeare mentions a dance “in country footing,” presumably a country dance (F1: Tempest, leaf B2r., p. 15). Choreographies for “country dances” started appearing in 1651, with the publication of PLAYFORD: The English Dancing Master London 1651

[17] For a summary of dance sources pertaining to Shakespeare’s plays, see MONAHIN: “Decoding Dance” (Appendix 1 and 2). In: MCCULLOCH / SHAW (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Dance. New York 2019, p. 78-82

[18] For Inns of Court dance sources see DAYE / THORP: “English Measures” 2018, and DURHAM / DURHAM: “The Old Measures” 2001. http://www.peterdur.com/pdf/old-measures.pdf

[19] ARBEAU: Orchésographie Langres 1589 / English transl. Orchesography New York 1967

[20] For more on dance connections between England and the Continent see DAYE: “Graced with Measures” 2013 / RAVELHOFER: Early Stuart Masque 2006, p. 16-20; p. 29 / MCGOWAN: Dance in the Renaissance 2008, p. 12, p. 15-16 / NEVILE: Dance, Spectacle 2008, p. 13-16 / NEGRI: Gratie, p. 2-6, provides a long list of names of his colleagues and disciples who were employed at European courts.

[21] For information on the role and status of torchbearers in the English masques, see DAYE: “Torchbearers” 1998, p. 246-62

[22] TABI: “Editing Shakespeare” 2003, p. 2 discusses this scene from the point of view of editorial practice and comments that: “it is evident from the Quartos that Romeo and his friends would march from the street to the Capulet house without any change of scene on the Renaissance stage–thus retaining the fluidity of action.”

[23] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet 1599 [Q2], leaf C2v.

[24] Immediately after the direction for servants to enter with napkins, Q2 has a stage direction, “Enter Romeo” (leaf C2v.), which may be an error because in F1 it has been changed to “Enter Servant” (leaf 2e5r., p. 57). Shakespeare distinguishes between the main servant who is designated as “Servant” and the assistant servants who are simply listed by numbers: “1,” “2,” and “3.” It thus appears that the assistant servants enter first, and begin their chores, and the main servant follows and starts giving orders.

[25] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet 1599 [Q2], leaf C3r.

[26] TABI: “Editing Shakespeare” 2003, p. 11, cites several scholars who share this opinion.

[27] SHAKESPEARE: [Romeo and Juliet, F1] 1623, leaf 2e4v., p. 56

[28] For more on the influence of the Tudor masque on Shakespeare, see DILLON 2007, p. 58

[29] DAYE 1998, p. 247

[30] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet 1599 [Q2], leaf C1r.

[31] Perhaps they do no more than march, or perhaps they use dance steps, such as the allemande double step described by Arbeau, which consists of three steps forward on 3 counts, and a following through of the rear foot to the front on the 4th count. (ARBEAU: Orchesography 1967, p. 125-127) However one does it, I think Capulet and his guests should be able to observe at least the tail end of this procession.

[32] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet 1599 [Q2], leaf C3r.

[33] Although the line “Ah, sirrah, this unlook’d-for sport comes well” is often viewed as being addressed to Capulet’s old cousin, various scholars have noted that “sirrah” is usually an address to a younger person, or, when preceded by the interjection “ah,” to oneself. (TABI: “Editing Shakespeare” 2003, p. 20). Capulet may be commenting to himself, which would mean that his next line, which is addressed to his cousin, does not need to follow immediately.

[34] For the Hampshire Shakespeare Company production, for the first dance, I adapted sections of “La Caccia d’Amore” (from Cesare Negri’s Le Gratie d’Amore), beginning with a processional figure, and moving on to a section near the end when men try to steal other men’s partners. I thought it would be amusing to have Capulet’s old cousin try to join the dance in this way. I would probably not use “La Caccia” today, as I think it might be too boisterous for an opening dance. A branle might be a better choice. I have therefore rethought how to incorporate Cousin Capulet, and I would now have him reaching for a candle at the start of the second (candlestick) dance, as I show in my chart.

[35] ARBEAU: Orchésographie 1589, p. 86-87; Orchesography 1967, p. 161-163

[36] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet [Q2] 1599, leaf C4r.

[37] See BRISSENDEN: Shakespeare and the Dance 1981, p. 65. The inspiration for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is believed to have been a 1562 narrative poem by Arthur Brooke, titled The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, which itself was based on earlier sources.

[38] See WINEROCK: “We’ll Measure Them a Measure” 2017 for other staging possibilities.

[39] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet [Q2] 1599, leaf C3v.

[40] To make this more amusing, in the Hampshire Shakespeare Company production I had Paris place himself in Juliet’s way so that she had no choice but to choose him and dance with him again.

[41] This could possibly be alleviated by having the change in dances take place during the last part of the Tybalt/Capulet altercation, so that the new dance (and one as simple and unobtrusive as possible) would have a chance to become established in the viewers’ minds before Romeo and Juliet start speaking.

[42] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet [Q2] 1599, leaf C4r.

[43] SHAKESPEARE: Romeo and Juliet [Q1] 1597, leaf C4r.

[44] SHAKESPEARE: [Much Ado, F1] 1623, leaf I4v., p. 104

[45] The Inns of Court dance manuscripts list the measures first. Of those that include other dances, all but one list either the cinquepace or galliard immediately after the measures. Further evidence is found in CANNING: Gesta Grayorum London 1688, p. 20, p. 44, which has references to entertainments at the Gray’s Inn in 1594, where the measures “and their galliards” were danced. Although the terms “galliard” and “cinquepace” were often used interchangeably, many sources indicate that the galliard included variations (called “tricks” in England), while the cinquepace employed mainly the basic “five steps.” For a detailed discussion of the differences between the cinquepace and the galliard, see MONAHIN: “Decoding Dance” 2019, p. 54-58.

[46] SHAKESPEARE: [Much Ado, F1] 1623, leaf I4v., p. 104

[47i] I have discussed this staging and my reasons for choosing several measures in MONAHIN: “And So Dance out the Answer” 2015. My tables in the present article, showing the correspondence between the text and the movements, are taken from that article and are reproduced here with the publisher’s permission. See also MONAHIN: “Decoding Dance” 2019.

[48] Various other explanations have been proposed for this seeming anomaly. An interesting explanation was proposed by WINEROCK: “Licence to Speak” 2021, p. 54, who suggested that the practice of disguising may be partly responsible. For, although only the man is wearing a face covering, the fact that his identity is hidden affords not only him, but his partner too, more freedom of expression. This seems very plausible, although I think that Hero’s embarrassment also plays a large role, as well as some possible prior coaching by Beatrice.

[49] The Black Almain appears in several of the Inns of Court manuscripts. I used the version from the Douce 280 manuscript in the Bodleian Library (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 280, folios 66(a)v-66 (b)v. ca. 1609), which has been reproduced many times. See DURHAM / DURHAM: “The Old Measures” 2001. http:/ /www.peterdur.com/pdf/old-measures.pdf

[50] SHAKESPEARE: [Much Ado, F1] 1623, leaf I4v., p. 104

[51] The Hundred Merry Tales was one of several popular jest books from Shakespeare’s time.

[52] The Inns of Court manuscripts list the measures in a particular order, with the Black Almain last. After the measures it was customary to dance the cinquepace, as noted earlier.

Citation

Monahin, Nona. “Negotiating Text and Movement: Some Challenges in Staging Dance in Shakespeare’s Plays.” The Shakespeare and Dance Project, edited by Linda McJannet and Emily Winerock, November 26, 2024. https://shakespeareandance.com/articles/negotiating-text-and-movement/. Accessed [date].

Updated November 26, 2024.

2013-2026. All rights reserved. The Shakespeare and Dance Project.