by Leigh Witchel

Note

This talk was originally presented at the Danser Shakespeare / Dancing Shakespeare conference at Sorbonne University, Paris in November 2023.

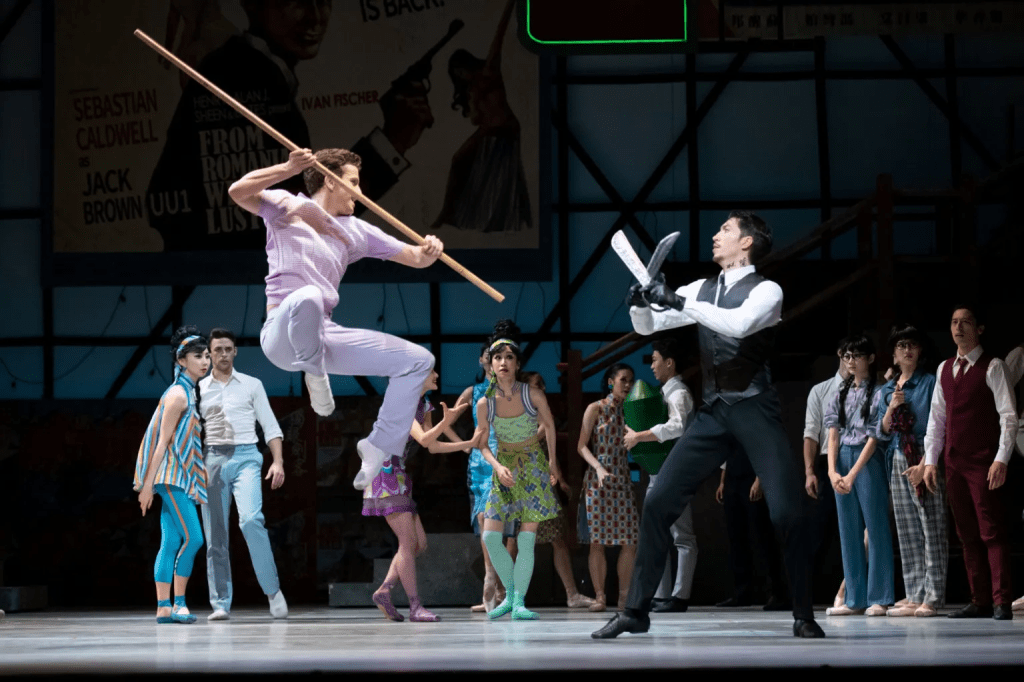

Photo credit © Christopher Duggan.

It isn’t groundbreaking to say that story ballets take on a life of their own beyond their source material. But it’s still illuminating to track the course of that journey. Two less-common productions of Romeo and Juliet, Francis Patrelle’s version originally made for Berkshire Ballet and Septime Webre’s production for Hong Kong Ballet, are useful examples of how a performance text with its own life emerges. In one instance the choreographer started largely from scratch, using his own interpretation of Shakespeare’s play as the source. In the other, the choreographer worked from earlier models, and the frame was built on earlier versions of the ballet. And often, performance details from prior versions adhered themselves to become part of the text.

There are productions of Romeo and Juliet based on other scores, but for this discussion, we’ll be working with these versions built on the score by Sergei Prokofiev. It’s one of the most recognizable dance compositions of the 20th century, and like the score of Swan Lake, far from the composer’s original intentions, which included a happy ending.

Prokofiev’s collaborators for the story’s treatment were the dramaturge Adrian Piotrovsky and the director Sergei Radlov. The shadow authors of the score were History and Politics. The production was tabled for several years as the Soviet Union plunged further into a period of artistic repression. Radlov fought with the Kirov Theater, where the idea originated, and moved to the Bolshoi. Piotrovsky, who was attacked for his libretto for The Bright Stream, was arrested and then executed in 1937.[1]

The ballet’s first performance was in an abridged production built from Prokofiev’s musical suites, done in 1938 in Brno, Czechoslovakia, a land occupied and soon to be plunged into war. Prokofiev was restricted from traveling and could not see it.

The ballet was finally performed at the Bolshoi in 1940, in a rearranged and reorchestrated version that involved many hands and restored Shakespeare’s tragic ending. Ironic that Prokofiev’s intended bowdlerization of Shakespeare was itself censored, not just by the political administration, but by collaborators such as conductor Yuri Fayer.

But like Swan Lake, this edit, shaped not by the artist’s original intent, but by politics and the cold realities of performance, endured because it worked. It told the story cleanly, and had all the necessary ingredients to make it a ballet, including solos, group numbers and three major duets for the lead couple. Its clarity was enhanced by Prokofiev’s use of leitmotifs for the main characters.

Choreographically, there is no single canonical version of Romeo and Juliet. As with The Nutcracker, canon and tradition is local. In Russia, the 1940 Bolshoi production directed by Leonid Lavrovsky that effectively created the performance score of the ballet was supplanted by Yuri Grigorovich’s version. In New York and London, the benchmark version is largely Kenneth MacMillan’s; in Stuttgart, it’s John Cranko’s; and so on.

Even with ballets for which we have, more or less, a canonical version—Giselle likely being the best example, Swan Lake more problematic, Perrot or Petipa would likely not recognize large chunks of the “traditional” versions. You learn that “tradition” is merely what you grew up with.

In New York, The Joffrey Ballet first performed the Cranko in 1984, and American Ballet Theatre gave its premiere of MacMillan’s version in 1985. But because The Joffrey Ballet moved to Chicago, and ABT has retained the MacMillan production to this day, it became much more familiar in New York City. If you asked dancers from New York City to tell you the story of Romeo and Juliet, chances are they would tell you not Shakespeare’s story, but the plot of MacMillan’s ballet.

I’m a dance writer rather than an academic, so most of my work is done with primary sources: performances, videos, interviews, and my own viewing experiences and memories. For this piece, I began with what I recalled from seeing the works and checked videos. Then, as both Francis Patrelle and Septime Webre are colleagues, I called each to do an interview and gain additional perspective.

Patrelle’s Romeo and Juliet was originally made in 1982. I saw it in 1993, when he restaged it for his group in New York City, Dances Patrelle. He’s now 76 years old, and very gregarious.

This is his account of the work’s development.[2] Patrelle trained at the Juilliard School and had been choreographing at Berkshire Ballet, now Albany/Berkshire Ballet, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in the northeastern United States for a few years, while being based in New York City. To quote, “It was my first full length, but I wasn’t a child.” Another choreographer had been commissioned to create a version of Cinderella, but Patrelle was asked to fix it. He agreed, on the condition that he was allowed to make Romeo and Juliet.

In 1982, Cranko’s and MacMillan’s versions of the ballet were not yet in the repertory of New York’s resident companies. Before that, ABT had done a one-act version by Antony Tudor to music by Frederick Delius, which had been out of repertory about 10 years. As Patrelle said, “I hadn’t seen the MacMillan—maybe once.” He had fewer precedents to rely on.

Then he said, “I thought it was my job to tell the story.” That sounds innocuous, but it’s the heart of this discussion. Which story? Shakespeare’s or Prokofiev’s? Despite questions and variants, Shakespeare more has a text than less. By its nature, dance has less of a text rather than more. We have no choice but to venture away from text, and this is both a problem and an opportunity.

Patrelle, having to forge his own path, chose Shakespeare’s story. Ballet is a form that is more influenced by visual precedents than literary ones. But here, Patrelle was trying to source from the play. He read the play and blocked the narrative out on index cards, which he still has.

The genesis of this paper was my memory of scenes that were not usually in versions made to the Prokofiev score: a scene involving the failed delivery of the message from Friar Laurence and a long reconciliation of the warring houses at the end.

The message scene took some ideas from the play, but went its own way. Friar Laurence had a young attendant boy who was entrusted with taking a letter to Romeo about Juliet’s plan. While en route, he was waylaid by a group of street urchins.

Patrelle recalled that idea coming to him as he was sitting at the ballet’s studios looking out the window onto North Street, Pittsfield and pondering what to do. “We’ll have plagues!” In the play, the message was not delivered because a house was quarantined because of suspected plague, something that was recounted rather than shown. To make that idea dance, Patrelle created plague victims. While on his errand, the young boy was stopped and killed by them; as Patrelle explained, he was literally felled by the plague.

Another digression from other versions, and even more so the score’s libretto, is that there was no tomb scene pas de deux. The deaths happened onstage relatively quickly, and then much of the music was instead used for a reconciliation of the Montagues and Capulets.

As with so many things in ballet and performance, the reasons were more practical than philosophical. Patrelle didn’t think he had the cast for a tomb scene pas de deux. Did skipping the tomb pas de deux work? It did create a forced symmetry with the unsuccessful truce after the street fights in Act 1. But it was a problem, because it fought Prokofiev. The composer used leitmotifs; you heard a theme associated with Juliet but you saw her lying dead in a wheelbarrow.

As Patrelle said, “I’m not making a pretty ballet, I’m telling a story.” Tudor had taught Patrelle at Juilliard, and as Patrelle paraphrased his advice, “You can make your point, you have to do it again, and then when you think the audience is bored of it, you pound it into them so they understand.”

Yet, how much does a story ballet need to actually tell the story? To quote myself from a 2014 Ballet Review piece covering Christopher Wheeldon’s adaptation of another of Shakespeare’s plays, The Winter’s Tale:

A dancemaker as experienced as Wheeldon can recognize the obvious dangers of adapting a towering wordsmith into dance, and he stated them succinctly in a preview video: “The biggest challenge for any choreographer tackling Shakespeare is to somehow infuse the poetry into the movement and not rely on the plotline.”

And like a man who so determinedly tries to avoid a hole that he might fall right into, Wheeldon did exactly that.

Though he shaved down the narrative and cut characters, like an icebreaker in the Northwest Passage, Wheeldon spent vast amounts of time trying to plow through the plot.[3]

This conundrum illustrates why most successful story ballets use very familiar plots. Dance narrative isn’t an oil painting; it’s a watercolor. Narrative details are implied. What can be painted vividly besides movement is mood. This is another impetus for ballets to move away from their source material.

Before continuing, I’d like to honor the memories of Alexandra Kinter and Jana Fugate. Alex was the lead “plague dancer” in Patrelle’s production when it was done in New York City. I knew her from class at David Howard’s studio; she passed away in 2007 at the age of 37. Jana was Patrelle’s original Juliet in 1982 at Berkshire Ballet. When we were lucky at Gabriella Darvash’s studio in New York City, Jana would be in town and taught an excellent class. One very fond memory I have was serendipitously getting to partner her during a workshop rehearsal of Valse Fantasie. Jana died at the age of 51 in 2011. Both women are greatly missed.

Patrelle wanted to use Shakespeare as the main source of his narrative. The first thing Septime Webre said during his interview, which included his reactions to reading my review of his production, was that he agreed that it was Prokofiev’s libretto, not Shakespeare’s.[4]

Webre’s version was created in 2021 and toured to New York City in 2023. Though it was a major achievement, I won’t go into detail about the transposition of the location to Hong Kong. I will be talking about the production’s sourcing from previous productions.

There are many productions of the Prokofiev ballet to use as models, but Webre’s seemed to be tracking MacMillan’s 1965 production for the Royal Ballet. With a few alterations, this paralleled that versions’ plotline, and the details kept or changed seemed like riffs or reactions.

For me, the first hint of the source was one of the quotes that was specific to MacMillan. The Amah, Webre’s Hong Kong transposition of The Nurse, stood behind Juliet and gently pointed to Juliet’s breasts to indicate that she was no longer a child.

Webre confirmed the influence of MacMillan’s version when we spoke. He had seen the Cranko setting on video, and live perhaps once. To quote him, “MacMillan’s was in my psyche and a big strong influence.” At the same time, he hadn’t actually seen MacMillan’s version all that much either. His estimate of the last time was probably two decades before he made the current one, in 2001, and he remarked that it “felt a little musty.” However, in an article from Asia’s Tatler in 2020, Webre said, “I’ve seen it 25 times and MacMillan’s remains my favorite.”[5]

Webre himself felt the echoes of MacMillan most in the pas de deux. His Act 3 bedroom duet certainly contained these echoes: Juliet pitched herself into en dedans turns in Romeo’s arms as in the MacMillan; then Romeo spun her into lifts.

At the conclusion of our interview, Webre again referred to my review, where I said that even though the quote of the Nurse and Juliet made clear the sourcing, it seemed to come from nowhere and was one of the few that didn’t resonate.[6] He agreed with me, and said he almost took it out. “It makes sense because there’s a musical button.” I’m not entirely certain though if he said this because he meant it, or because he was talking to me. Welcome to the hazards of oral history.

There are certain other memorable details that are part of MacMillan’s production and not Cranko’s. In Act 1, after Juliet and Romeo have met and danced together alone, Tybalt caught the couple and the family returned to the scene. There’s a disturbing squeal in Prokofiev’s score: MacMillan had Tybalt point accusingly at Romeo at that moment. Webre brought that detail into his version.

Webre is a magpie, and he and his team risked fate by inviting consistent comparison with other versions of the story. There were even echoes of the dances for The Jets in West Side Story, as Romeo, Little Mak, and Benny (as Mercutio and Benvolio were called in this version) circled before their Act 1 trio, jumping in a crouch, antic and gymnastic, tumbling off one another.

But Webre’s staging wasn’t just, as you might see in a smaller company with a tight budget, an in-house copy of an expensive dress. Nor was it just a transposition from Verona to Hong Kong. It was a reaction to and reflection on the ballet itself.

Another MacMillan tableau is in Act 3. The music swelled, and MacMillan had Juliet retreat to her bed and sit, motionless, as the music swirled round her. It’s a moment that’s burned into a lot of folks’ idea of the ballet. I saw Natalia Makarova in that moment when ABT first staged the production in 1985 at The Metropolitan Opera House in Lincoln Center. I wasn’t yet 22. At that moment, dwarfed by the massive stage, Makarova was so fragile, but so much larger than life, that I bought standing room tickets for all the rest of her performances.

Webre made a wry acknowledgment to that moment. He had Juliet sit on her bed in that pose, but for a short time, and not at the same music, but later on. Seeing that in New York, it felt like a kind of fan service. What’s important to this discussion is that Webre wasn’t reacting to Shakespeare here. Those things aren’t in Shakespeare. He was reacting to MacMillan and Prokofiev.

There are some details within MacMillan’s version that, if that’s the version you know best, feel like part of the text. Further, there are conventions in more than MacMillan’s version of Romeo and Juliet that are part of an accreted performance tradition and don’t come from Shakespeare: for example, Rosaline becoming an onstage character instead of only being mentioned; Escalus and Friar Laurence being played by the same character dancer; Lady Capulet and Tybalt having an affair.

All of these found their way into Webre’s version, and they come from previous versions. In a few cases he pushed them farther. He took the double-cast role of Escalus and Friar Laurence and combined the two men into a sifu, a wise mentor to Romeo.

Even the MacMillan version, from staging to staging and performance to performance, has variations that go beyond choreography to arguably plot elements. Shakespeare’s play has a stage direction that Tybalt stabs Mercutio under Romeo’s arm. Webre’s version is more straightforward: Tai Po (this version’s Tybalt) and Little Mak fight, and Tai Po slashes him under the arm.

At ABT, it seems to be left up to each cast exactly how Mercutio gets killed. In many recent performances, it’s been almost an accident. Mercutio and Tybalt have fought, but after talking with Romeo, Mercutio backs into Tybalt’s sword. That’s a good step away from Shakespeare.

The death of Romeo and Juliet is also an area where various productions go their own way. One of the most surprising was Alexei Ratmansky’s production for the National Ballet of Canada in 2011. In that, Romeo took poison, but saw Juliet stirring and realized she was still alive just as he died.

A smaller elastic point in ABT’s production is whether or not Juliet reaches Romeo after stabbing herself. There isn’t absolute freedom here, every Juliet winds up in the same general pose, across the bier, arching her back, but she does seem to have a choice as to whether to clasp Romeo’s hand or never make it there. This is ballet, though. What isn’t optional seems to be that Juliet dies in parallel position with her feet pointed.

Photo credit © Christopher Duggan.

Going back to Webre, he acknowledged the influence of MacMillan both on this production and the first production of Romeo he did, in 1994 when he assumed the leadership of American Repertory Ballet. But the biggest influences, to quote him, were “the ‘94 production and the way I’ve changed.”

Then what influenced the 1994 production? Webre was forthcoming. When he was studying dance in Austin, Texas, his teacher, Stanley Hall, mounted a production of Romeo in which Webre danced Tybalt. It “was so successful to me,” he shared. That’s the version that Webre grew up with.

And what influenced that version? Hall was an early member of the Vic-Wells Ballet, which later became The Royal Ballet. After the war, he danced for Roland Petit, then in America, but his version of Romeo and Juliet was obviously influenced by MacMillan. The “point and squeal” from MacMillan, Webre actually took from his memories of Stanley Hall’s production. Same with the scene with The Nurse and Juliet. So MacMillan’s version, even outside of cities where it was in repertory, became influential via copies.

To stage Romeo and Juliet using Prokofiev’s score, you need to opt for whether you’re going with Prokofiev’s structure and libretto, or sticking with Shakespeare. We’ve looked at two different approaches, and I think that if you opt for Shakespeare, that’s going to be simpler if you aren’t following choreographic precedents. The places where there is the most latitude, as with plays, is what can be done that’s outside the text of the choreography, the script as it were. And yet, as time goes on, people follow and refer to the versions of ballets made before theirs, as we’ve seen from Webre’s influences: even the areas outside the script can gain the power of text itself.

Epilogue

Thank you all for sticking with me through my first conference talk. As I was writing this paper, and as discussions also sometimes take on a life of their own, this one whispered that it had a second topic it wanted to talk about: memory. Memory is the culmination of the act of witnessing, of being there. It’s what I hope I’ve done in my nearly three decades as a dance writer. Memory is neither perfectly accurate, nor reliable; it needs to be checked and corroborated. But the accretion of what we have seen and what we recall leads to another path of understanding dance, and our responses to it. And not just dance. The history we all share now, inside and outside the classroom or the theater, demonstrates the life or death importance, not of what happened, but of how we remember it happening.

Endnotes

[1] Katerina Clark, Petersburg: Crucible of Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), pp. 291-292.

[2] Conversation with Francis Patrelle, October 5, 2023.

[3] Leigh Witchel, “London,” Ballet Review, vol. 43, no. 3 (Fall 2015), p. 13.

[4] Conversation with Septime Webre, October 5, 2023.

[5] Zabrina Lo, “Hong Kong Ballet’s Artistic Director Septime Webre On Reimagining Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet,” Tatler Hong Kong, July 2, 2020. https://www.tatlerasia.com/lifestyle/entertainment/hong-kong-ballet-septime-webre-romeo-and-juliet.

[6] Leigh Witchel, “Transposition,” dancelog.nyc, January 31, 2023. https://www.dancelog.nyc/transposition-2/.

Citation

Witchel, Leigh. “Whose Romeo is it anyway?” The Shakespeare and Dance Project, edited by Linda McJannet and Emily Winerock, July 11, 2025. https://shakespeareandance.com/articles/whose-romeo-is-it-anyway. Accessed [date].

Updated December 22, 2025.

2013-2026. All rights reserved. The Shakespeare and Dance Project.